Series Introduction — Why Siddhartha Still Speaks to Us

This is the first part of a three-part reflection on Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, a book that has quietly endured for nearly a century and continues to resonate with readers across cultures and generations. Set in ancient India but written by a German author in the early twentieth century, the novel does not belong to any one time or place. Its questions are timeless because they arise wherever human beings begin to look beyond comfort, success, and inherited beliefs.

The deeper intention of this series is to explore the questions Siddhartha raises about meaning, ambition, restlessness, desire, suffering, and the long search for a life that feels authentic. Rather than asking what Siddhartha discovers at the end of his journey, these essays invite us to ask a more personal question: what might our own lives be trying to teach us?

Across these three parts, we will move through three phases that Siddhartha experiences, and that many people encounter in different forms throughout their lives. The first is the phase of the seeker, when life appears stable and respectable, yet something within refuses to feel satisfied. The second is the phase of immersion in the world, where success, pleasure, and identity slowly draw us away from ourselves. The third is the phase of return, when wisdom begins to grow not from rejecting life, but from accepting it fully.

What makes Siddhartha so enduring is that it does not offer a system or a set of instructions. Instead, it insists on something far more demanding: that each person must walk their own path, learn through their own experience, and accept that even confusion and mistakes may be part of the journey.

With that, we can begin where every genuine inner journey begins—not with rebellion or certainty, but with a quiet, persistent unease that refuses to disappear.

The Quiet Hunger for More

There comes a time in many lives when everything appears to be in order, and yet something feels subtly incomplete. Nothing is obviously wrong. Days pass smoothly, responsibilities are fulfilled, and from the outside life seems stable, even successful. Still, in moments of silence, a question returns with quiet insistence: Is this really all there is?

This dissatisfaction does not usually arise from failure. More often, it appears when things are going well. It belongs to people who have learned how to live correctly, but not yet how to live truthfully. Society offers ready-made paths, respectable roles, and clear definitions of success, and for a long time we may follow them without resistance. But for some, a point arrives when those paths begin to feel narrow, and those roles begin to feel borrowed.

This is where Siddhartha begins.

When we first meet Siddhartha, he is not struggling for survival or recognition. He is intelligent, admired, and surrounded by everything that should, in theory, make him content. And yet, beneath that well-ordered life, there is a restlessness he cannot ignore. He senses that there is a difference between knowing about life and actually touching its essence.

Many people recognize this feeling, even if they describe it differently. It shows itself when achievements no longer excite us, when routines feel mechanical, or when we sense that we are living according to expectations that are not entirely our own. It is not always a spiritual crisis, but it is certainly an existential one—a quiet conflict between the life we are living and the life we feel drawn toward.

Seeking, in this sense, is not an escape from responsibility. It is often the first honest response to an inner truth that has been ignored for too long. Siddhartha’s journey begins not with drama, but with this deeply human experience: the realization that comfort and respectability are not enough to silence a deeper hunger.

Siddhartha: The Ideal Son Who Wasn’t Satisfied

Siddhartha grows up in circumstances most people would consider fortunate. Born into a respected Brahmin family, he receives a careful education and quickly becomes known for his discipline, intelligence, and spiritual promise. His father is proud of him, his teachers admire him, and his close friend Govinda looks up to him with quiet devotion. Everything about his early life suggests a future that is secure, honorable, and admired.

Yet very early on, Siddhartha begins to sense that something essential is missing.

He studies the sacred texts, performs the rituals, practices meditation, and follows the spiritual disciplines expected of him. But whatever peace he gains does not last. The calm fades, and the same questions return. Slowly, he realizes that he is gathering knowledge without gaining inner clarity, and performing devotion without finding real transformation.

From the outside, Siddhartha looks like someone who has already found his way. From the inside, he feels as though he has not even begun. He can see clearly the life prepared for him—a respected priest, admired for wisdom and secure in his place in society. It is a good life, but the more clearly he sees it, the more he understands that it is not truly his.

Sometimes a life can be too perfect to question—until the questioning becomes unavoidable.

Siddhartha’s dissatisfaction is not driven by rebellion or arrogance. It comes from an honest intuition that truth cannot be inherited and wisdom cannot be lived on someone else’s behalf. Long before he knows what he will do, he knows this much: he cannot remain where he is.

The First Rebellion: Leaving Home to Find Truth

When Siddhartha finally acts on his restlessness, the decision does not come suddenly. It grows quietly from everything he has already understood. To stay would mean slowly betraying himself, even if that betrayal looked respectable from the outside.

He decides to leave home and join the Samanas, wandering ascetics who renounce comfort and possessions in search of liberation. This choice is not about rejecting his family or his culture; it is about testing himself against life directly, without inherited answers or familiar structures.

The moment he speaks to his father is one of the most powerful in the book. His father refuses at first, unable to accept that his gifted son would abandon everything prepared for him. Siddhartha does not argue. He stands silently through the night, unmoving, until his father understands that this decision is not stubbornness but necessity. By morning, with sorrow and dignity, his father gives his consent.

This is Siddhartha’s first real rebellion—not against authority, but against a life that feels second-hand.

Govinda, his closest friend, chooses to follow him. Govinda’s loyalty adds warmth to this departure, but it also foreshadows something important: while others may walk beside us for a time, the reasons we walk are always our own.

Leaving home comes with a cost. Siddhartha gives up certainty, belonging, and approval. He chooses hardship and uncertainty, believing that suffering may bring him closer to truth than comfort ever could. Many people recognize this moment in their own lives—in career changes, in resisting family expectations, or in choosing uncertainty over security.

What Siddhartha shows us here is not that rebellion is noble, but that sometimes staying is the greater betrayal. Growth often demands separation, not because the old life was wrong, but because it can no longer contain who we are becoming.

The Landmark Moment: Meeting the Buddha

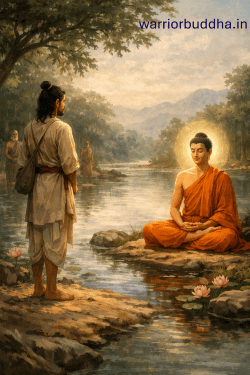

After years of discipline with the Samanas, Siddhartha hears of Gautama, the Buddha—a man said to have awakened fully and ended suffering. When Siddhartha meets him, he is struck not by authority or spectacle, but by a profound inner stillness. The Buddha does not persuade or impress. He simply is.

Siddhartha meets Buddha

Siddhartha immediately recognizes the reality of the Buddha’s enlightenment. There is no doubt in his mind about that. Yet listening to the Buddha’s teachings leads him to an unexpected realization. The teachings are clear and compassionate, but Siddhartha understands that the Buddha reached truth before there were any teachings at all. The path came after the experience.

This insight changes everything.

With deep respect, Siddhartha explains why he cannot become a disciple. What the Buddha has found, Siddhartha must find for himself. No matter how perfect a teaching may be, it cannot replace personal experience. Truth cannot be transferred without losing its essence.

Govinda chooses differently, staying with the Buddha and placing his trust in guidance. Their parting is gentle but decisive. Govinda chooses Buddha; Siddhartha chooses himself.

What Siddhartha learns in this moment is both liberating and unsettling: that even the highest wisdom cannot spare us from walking alone. Teachers can point, inspire, and illuminate—but they cannot live the truth on our behalf. Each person must encounter it directly, through their own struggles, mistakes, and insights.

In choosing not to follow, Siddhartha commits himself to the difficult task of becoming himself.

The Courage to Walk Alone

After leaving the Buddha, Siddhartha finds himself truly alone. There is no doctrine to rely on, no teacher to follow, no community to belong to. The certainty that once came from structure has dissolved, leaving openness—and with it, solitude.

This solitude is not heroic. It is unsettling. Freedom, Siddhartha realizes, carries responsibility. Without borrowed beliefs to lean on, he must face uncertainty directly. Learning gives way to living. Answers give way to experience.

Many people recognize this phase in their own lives, when guidance no longer satisfies and nothing clear has replaced it. This emptiness can feel frightening, but it is often where a more authentic life begins to form.

Siddhartha does not celebrate his independence. He accepts it. In doing so, he steps into a life that is no longer protected by certainty. What lies ahead is unknown, but it will shape him in ways discipline and imitation never could.

A Personal Reflection

When I first read Siddhartha in my early twenties, I did not understand all of it intellectually, but I felt unmistakably drawn to something at its core. What stayed with me most was not Siddhartha’s final enlightenment, but his refusal to accept ready-made answers—no matter how noble or revered they were.

The book seemed to suggest something both liberating and unsettling: that no teacher, no scripture, no ideal life can substitute for one’s own lived experience. Others may guide us, inspire us, or illuminate certain directions, but the actual journey—its doubts, detours, mistakes, and insights—belongs to us alone. Siddhartha’s life made it clear that even wandering, confusion, and apparent “wrong turns” are not necessarily deviations from truth, but sometimes the only way toward it.

This understanding shaped the way I began to look at my own life. It reminded me that following one’s inner calling is rarely neat or socially approved, and that the price of authenticity is often uncertainty. Yet it also suggested that living honestly, even imperfectly, is far more meaningful than living safely within borrowed ideals.

Questions for the Reader’s Inner Journey

Before moving forward, it may be worth pausing for a moment and asking yourself a few simple, honest questions—not to arrive at quick answers, but to listen carefully to what arises.

Are there parts of your life that look “right” on the surface, yet feel strangely disconnected inside?

Have you ever sensed that the path you are walking, however respectable, might not fully belong to you?

Whose approval or expectations still shape your decisions more than your own inner truth?

And if you allowed yourself to listen without fear, what direction might your deeper self be quietly pointing toward?

These questions do not demand immediate resolution. Like Siddhartha’s restlessness, they are meant to stay with you, to mature slowly, and to guide you when the time is right.

Closing: A Step Toward the World

By the end of this first phase, Siddhartha has not found enlightenment. What he has found is the courage to trust his own experience. Having walked away from tradition and teaching, he now stands at the threshold of a very different chapter.

The world he once observed from a distance—filled with desire, ambition, pleasure, and identity—now opens before him. He believes he can enter it without losing himself.

What he does not yet know is that life often teaches not through denial, but through immersion, and not through protection, but through loss.

In the next part of this series, Siddhartha steps fully into the world—and slowly begins to forget the questions that once guided him.

Sometimes, it is only by losing ourselves that we begin to understand what truly matters.

The journey continues…

Leave a comment